The Latest

The Only 3 Printing Techniques Every Art Collector Should Know

In this article, I want to introduce a framework for understanding art production that might change how you look at art as a whole. It developed gradually in my mind as I went through various printmaking courses and noticed how certain methods shared similar principles and values, while others though producing similar visual results relied on completely different processes…

In this article, I want to introduce a framework for understanding art production that might change how you look at art as a whole. It developed gradually in my mind as I went through various printmaking courses and noticed how certain methods shared similar principles and values, while others though producing similar visual results relied on completely different processes.

In practice, this meant that practitioners of different techniques often saw and valued different qualities in the final image. For example, a black-and-white inkjet print, a photogravure, and a screen print might look similar on paper, yet each is appreciated for distinct reasons: the inkjet for its tonal range, the photogravure for its depth of blacks and even tonality, and the screen print for its sharpness and controlled gradations.

Without a clear understanding of where a process sits conceptually and technically, there’s a real risk of chasing the wrong goal or using the wrong method to achieve a desired result. My aim here is to cut through the noise of technical branding—inkjet, giclée, offset, c-print—and focus instead on the underlying logic of how an image actually appears on paper: the principle behind the process that brings it into being, whatever name it carries.

You see, every image on paper—whether digital, mechanical, or ancient—comes from one of three fundamental principles governing the relationship between matter and surface: something is put on, something happens within, or something is pressed against. Paint is put on, a photograph develops from within, and a print plate is pressed against the paper. Every other process is simply a variation or combination of these three.

Once you understand the production principle behind each process, you’ll begin to form expectations. Those expectations are the foundation of genuine appreciation. Only when you know what to expect and an artwork exceeds it does real passion begin to grow. That’s when the desire to experience, own, and collect art becomes serious. You start to develop an instinct for how materials behave, what kind of skill each method demands, and what level of result can reasonably be achieved. Great art will meet or even surpass your expectations, pushing them to new levels. In that process, you grow not only as an art collector but also as a human being.

Eventually, you’ll start to see that each process shapes not only the image’s material qualities but also its emotional and symbolic weight. You’ll gain the ability to speak about authorship: the artist’s choice of medium, execution, and intended effect as well as the tactile and aesthetic character of the image itself. By the end of this article, I hope you’ll see art differently: not as a set of mysterious techniques, but as expressions of three fundamental processes.

Overview

Every image that has ever appeared on paper comes from one of three basic relationships between matter and surface.

First, there’s direct application — paint, ink, or pigment laid straight onto the paper. Brushes, pens, even the inkjet printer all do the same thing: they deposit material directly onto the surface.

Second, there’s chemical reaction — the alchemy of traditional photography, where the image forms within the fibers of the paper itself. Silver gelatin, platinum printing, cyanotype — all depend on light and chemistry rather than applied pigment.

And third, imprint and transfer — methods like intaglio, lithography, screen printing, or photopolymer. These use an intermediary surface that presses, stamps, or transfers an image onto paper through contact and pressure.

The application, reaction, transfer covers almost everything that can happen between paper and image. The few outliers, such as laser printing or embossing that modify the surface through heat, pressure, or burning, echoing the same physical logic as imprint and transfer.

Ultimately, this framework shows that all image-making comes down to the same three principles — the physical act that joins material and idea. A cave painting, a darkroom print, a laser print — all follow the same process: idea → contact → art. Once you grasp this, you’ll begin to read artworks through the logic of their chosen medium.

Let’s start from the top.

I.Direct Application

The direct application process is when something is applied directly onto the surface: paint on paper, walls, caves, or canvas. Most of the world’s art falls into this category: paintings, drawings, sketches. The application materials are the familiar tools found in any art store: oil, acrylic, watercolor, pencils, pastels, inks, and more. The surfaces range from various types of paper and canvas to wood and film.The defining feature of this method is its freedom: freehand application, open format, and a broad selection of materials and colors. The appeal of this format lies in its expressionism — the creation of one-off, unique works of art.

In photography, this principle is used in digital printing. Inkjet printers are essentially advanced painting machines, applying inks directly onto paper. The “hand” of the artist is replaced by mechanical precision, but conceptually it’s still direct application of color to surface, and the richness of color and variety of media remain. Laser printing mostly fits here too, though it technically involves an electrostatic transfer before fusing toner to the surface and hence it can be in both categories: direct application and transfer, hence it is a hybrid process.

Inkjet printing.

Inkjet print is often called “giclée” in the fine-art world. The word comes from the French gicler, meaning “to spray” - a nod to how inkjet printers work. In practice, giclée usually means a print made with archival pigment inks on archival paper. The term is meant to distinguish high quality archival prints from cheaper, dye-based inkjet prints. In reality, giclée is just another useless word that the art world invented that the rest of the world struggle to understand. Now when you know what it is, let’s just use inkjet prints in the rest of this article.

Inkjet prints are made by technologically advanced printheads that spray microscopic droplets of ink onto specially coated papers designed to absorb and hold those inks. The method began taking shape in the 1980s with work by Canon and HP, but it wasn’t until the early 2000s that Epson introduced printers capable of true photo-lab quality.

The main advantage of inkjets is consistency and scalability. Prints can be reprinted exactly, produced in very large sizes, and when made with pigment inks on high-quality papers, they can last for centuries. Inkjet printing is also relatively affordable and compact process compared to other printmaking methods which makes it appealing for many artists.

Beyond its technical precision, inkjet’s greatest strength lies in its range. Inkjet supports more paper types than any other process, and finding the right combination of ink, paper, and settings for an image is both a craft and a science. The quality of a print depends on matching the ink type—pigment or dye to the right paper type. As in painting, using oil on watercolor paper or watercolor on canvas will result in a messy painting.

But beyond the technical side, there’s also an emotional and tactile dimension. Most paper and ink combinations reproduce the image; only a few make it art. Hence, mastery in printing isn’t only about hitting perfect colors or tones; it’s about using the process to amplify the image’s visual power. Without that, a print is no better than a poster.

Once we place inkjet printing in this category, we’re inevitably reminded of its connection to traditional art-making. While inkjet printing can produce identical editions, the medium’s full potential lies not in mechanical perfection but in how the artist uses it to create nuance, individuality, and character. The goal isn’t to produce hundreds of flawless reproductions, but to make each print expressive and slightly unique. Many great printmakers deliberately introduce variation through paper choice, color grading, overpainting, embossing, or mixed-media intervention to preserve individuality and artistic presence.

II.Chemical reaction

A chemical reaction process refers to a method of image creation in which the photograph is formed by a chemical transformation that happens within the paper’s fibers rather than on its surface. Light-sensitive compounds embedded in the emulsion that covers a paper react to exposure and development, turning invisible particles into visible silver or pigment. Unlike inkjet printing, where ink sits on top of the paper, these chemically produced images become part of the material itself—literally built into the structure of the print. All processes in this category follow a similar sequence: the paper is coated, exposed to light, the chemistry is activated, the reaction is stopped, the image is fixed so it becomes stable, and finally washed and sometimes toned. The essential elements are always the same—chemical, light, and water—working together to turn a blank sheet into a lasting image. This means that only papers capable of withstanding repeated chemical baths and prolonged exposure to water can be used. They must be strong, well-sized, and stable enough to hold the emulsion without warping, tearing, or breaking down during processing.

The defining principle of this category is that images are developed by nature through chemistry, light, and water and yet the human hand is always present in the process: coating, developing, toning. Mastery lies in the artist’s ability to control these natural variations. In darkroom printing, skill means managing variables: time, temperature, dilution, and agitation to achieve reliable results from inherently unstable conditions. That’s genuine mastery.

With inkjet printing, the challenge is reversed. The process is built for consistency, so artistic expression comes from deliberately reintroducing variation—adjusting color, material, and presentation to recover individuality within a mechanical system.

To summarize: in inkjet printing, we’re often impressed by added variation; in chemical processes, we’re impressed by control—the ability to produce consistent results time after time. Despite their technical differences, both forms of mastery reflect a deliberate choice to work through complexity rather than settle for convenience—each valued for taking the harder, more intentional path.

Silver Gelatin

Silver gelatin is the classic darkroom print: light hits silver-halide paper, the latent image is developed, fixed, and washed. Its legacy is the “photographic look” many people picture in their head—deep blacks, luminous midtones, and a physical sheet that records the hand of the printer through dodging, burning, and toning. A silver gelatin print has a density and presence that is hard to describe until you see one in person. The image doesn’t sit on the surface of the paper, as it does in inkjet - it lives inside it. Light passes through the emulsion and reflects back, giving the print a subtle, almost three-dimensional depth. Blacks are more complex, highlights more luminous. When handled well, a fiber-based silver print has a tactile richness that digital paper simply doesn’t reproduce.

There are two main ways to producing a silver-based photographic print. The first is the traditional darkroom process: the film negative is placed in an enlarger, projected onto resin-coated (RC) or fiber-based (FB) silver gelatin paper, then developed, stopped, and fixed. After that comes an extensive wash to remove residual chemicals, followed by careful drying and flattening. Hand printing in this context involves a high degree of manual control like burning and dodging to balance light, split-grade printing to fine-tune contrast, and a meticulous attention to chemical timing and paper handling. While there are many development processes and papers fiber-based baryta papers defined the look of 20th-century photography for their tonal depth and longevity, demand particularly careful washing and drying to avoid stains and curling.

The second way is digital-to-silver printing, where a digital file is exposed onto silver paper using laser systems such as Lambda or LightJet. The exposed paper is then processed in RA-4 chemistry for color or in black-and-white chemistry for panchromatic silver papers. Color prints made this way are known as C-prints (chromogenic prints). They use the same chemical development process as traditional color darkroom prints, only with the initial digital exposure instead of an optical one.

Unlike traditional darkroom materials, Lambda and LightJet papers are specific to this process. They come in large resin-coated (RC) rolls, optimized for laser exposure and machine development. After exposure and development, the print is washed and dried much like any silver print. These papers deliver exceptional color consistency and sharpness, and the system allows for much larger prints than would ever be practical in a darkroom. However, they lack the tactile depth and slight surface irregularities of hand-processed fiber papers.

Both methods produce true silver photographs, but the first is rooted in manual craft, while the second relies on digital precision and scale. Collectors and galleries often prize hand-printed fiber photographs for their individuality and physical character, while Lambda or LightJet C-prints are valued for their clarity, color accuracy, and size. Each reflects a different balance between craft and technology.

Silver gelatin once defined photography itself. Today, it represents a deliberate artistic choice. Its appeal lies in the physical and aesthetic qualities of the process. A well-processed fiber print can last for a century or more - we still have 150-years old prints from the very beginning of photography. Choosing to print an image this way today signals that the photographer wants it to survive physically and culturally long after a digital file would disappear.

Perhaps the strongest reason to use silver gelatin today is authorship. It offers the photographer the chance to create a true, limited-edition print—an object touched and shaped by hand. Working in the darkroom forces a slower rhythm, a physical engagement with every step. The process is unpredictable, sometimes frustrating, but always human. Each print carries the traces of its making: tiny variations, decisions, hesitations. It is not mass production; it is a dialogue between light, chemistry, and touch. Silver gelatin printing endures because it transforms the photograph from an image into an artwork with photographic legacy.

Alternative Printing Processes

Besides Silver Gelatin printing there are “alt,” processes form a vast family of hand-crafted printing methods that trace photography back to its earliest material roots. The term covers a range of techniques—cyanotype, Van Dyke brown, platinum/palladium, carbon transfer, salt, gum bichromate, and many others. Most of them were invented between the 1840s and early 1900s and were the standard of their time until silver gelatin and later color processes took over as the default photographic process. The processes may use different chemicals, but the principle is the same: the image is formed within the paper itself through a chemical reaction, not simply deposited on its surface as inkjet prints.

The appeal of these alt.processes lies in materiality and authorship. Everything is made by hand: the paper is coated with chemistry, exposed under UV light, developed, and washed by the artist. Each stage—choice of paper, mixture of chemicals, humidity, exposure curve, and drying method—leaves visible traces in the final print. Nothing about it is automatic. These methods are slow, deliberate, and deeply tactile, giving the artist control over the image in ways no mechanical printer can. Many alt-process prints are also incredibly stable, rivaling or surpassing silver gelatin in longevity.

Cyanotype is perhaps the most familiar of these processes, known for its deep Prussian blue tone. The paper is hand-coated with ferric salts, exposed under UV light using a contact negative, and then washed in water to reveal the image. The result has a soft roll-off in the highlights and a graphic, high-contrast quality that feels timeless. Variations are endless: multiple coatings increase density, and different toning methods can shift the color from blue to brown, yellow, red, or violet, transforming the print into something entirely new. The creative appeal of cyanotype lies in its simplicity and low cost, which invite experimentation. Cyanotype can be printed on almost any surface—textile, ceramic, wood, stone, or tile—making it one of the most versatile and playful photographic processes ever invented. Inkjet or silver gelatin prints, for example, can be overcoated with cyanotype solution to create double exposures.

Left: Cyanotype washed and hung to dry; as it dries, the blue deepens.

Right: Cyanotype toned to varying degrees with coffee. The framed piece hides the brush strokes with a mat, but it could be displayed without the mat to reveal the hand‑made texture and brushwork.

Van Dyke brown, and its close relative the kallitype, use silver salts rather than iron in cyanotype. The paper is coated, exposed, developed, and fixed, producing warm brown images with delicate highlights and an antique sensibility. The tone depends strongly on the paper base, and toning with gold or selenium can deepen color and extend permanence. Cyanotype and Van Dyke Brown sit next to each other historically and technically, but they deliver very different visual and material results, and the process itself differs in complexity - Van Dyke Brown is more fragile, slower, and demanding process. It uses silver-based chemistry which immediately raises the level of sensitivity, cost, and care required - more steps, more precision, less forgiving process. Visually, Van Dyke Brown offers something closer to what we associate with early silver photography—sepia tones, delicate highlights, and a smoother tonal range than cyanotype’s punchy blues. Its surface looks softer, more classical. If cyanotype feels graphic and immediate, Van Dyke feels nostalgic and contemplative, leaning toward the emotional end of the spectrum and produces richer tonal depth. The advantage of this method is aesthetics - the print looks aged the moment it’s made, not through imitation but through material truth. It feels like an artifact, not a reproduction. For artists working with ideas of memory, decay, time, or tactility, that surface quality is inseparable from the meaning of the image. In a world of polished surfaces and instant results, it reminds both maker and viewer that photography once required touch, time, and a certain humility before chemistry and light.

Platinum and palladium printing - often referred to simply as Pt/Pd, occupies the top tier of historical photographic processes. It is the most refined and prestigious printing method ever developed, holding a special place among serious collectors and master printmakers. The paper is hand-coated with ferric oxalate mixed with platinum and/or palladium salts, then exposed to UV light and developed in a chemical bath before being cleared and washed. Every variable matters: humidity, paper sizing, coating consistency, and even room temperature can influence the final tones. The results are extraordinary - a matte surface with an exceptionally long tonal range, deep yet delicate shadows, and luminous highlights. Pt/Pd prints are among the most permanent photographic materials ever made, with an estimated lifespan of a 1000 years or more; the paper will disintegrate long before the image itself fades. With digital negatives, the process can be scaled to almost any size, but each print remains extremely expensive to produce because it uses real platinum and palladium metals. Photographers who work in Pt/Pd printing have usually mastered other alternative processes before arriving here. The cost of error is high, and the learning curve is steep. Yet the results justify the risk exclusive limited-edition prints often sell for thousands of dollars, even at small sizes. Pt/Pd printing stands as both a test of skill and a declaration of commitment: the point where craftsmanship, chemistry, and permanence meet.

The carbon transfer process is perhaps the most complex and labor-intensive of all alternative printing methods. It begins with the creation of a pigmented gelatin “tissue,” which is exposed under UV light and then transferred onto fine art paper in a delicate, temperature-controlled development. The resulting image is not just visible but physically present—the shadows rise in subtle relief on the surface. The texture is utterly matte, the blacks are deep and velvety, and the permanence is unmatched. It doesn’t look printed; it looks formed.

Multi-layer carbon transfers can even produce color images, each layer made from a different pigment, building a depth and richness that no other process can match. Artists continue to use carbon transfer today for its expressive potential. It offers unrivaled control over tone, relief, and color, and because every print is handmade, no two are ever identical.

Permanence is another defining quality. The image consists of pure pigment suspended in hardened gelatin—not dye, not silver. Properly made, it is virtually immune to fading. Museums regard carbon transfer as one of the most stable photographic processes ever developed; a print made today will almost certainly outlive every other type of photograph.

Yet, carbon transfer is expensive and rare, not because it relies on rare materials like platinum or palladium, but because it consumes time, focus, and skill. A single finished print may take hours or even days to complete, and several attempts might fail before one succeeds. It is a process that demands patience and commitment, and rewards them with something no other photographic process can.

Salt printing and its later cousin, the argyrotype, belong to the earliest generation of photographic processes—images literally made of light and salt. Paper is first soaked in a salt solution, then coated with silver nitrate to form light-sensitive silver chloride. The exposed paper yields a warm brown to reddish tone with soft, romantic highlights that seem to glow from within the fibers. Salt prints are delicate and atmospheric, with a sense of air and distance that no modern print quite captures. Argyrotype, developed as a contemporary update, simplifies the chemistry while keeping the same visual warmth and handmade texture. Both processes attract artists seeking that early photographic feel—light rendered as a gentle residue rather than a hard record.

Gum bichromate printing pushes photography toward painting. The process uses gum arabic mixed with pigment and a light-sensitive dichromate, hand-coated onto paper and exposed under a UV source. The unexposed gum washes away, leaving a softly pigmented image. The beauty of gum lies in layering: multiple coats can be applied, each with a different pigment, allowing the artist to build color photographs through tri-color gum printing. The result is tactile, textured, and deliberately imprecise—more a conversation between image and gesture than a mechanical reproduction. Gum prints are often unique hybrids, where brush marks and irregular edges become part of the artwork’s voice.

Oil and bromoil printing belong to the expressive end of historical photography, where image meets painting in both texture and spirit. In the bromoil process, a silver gelatin print is bleached and hardened so that its surface will accept lithographic ink—the darker areas absorb more ink, the lighter ones less. The result can be brushed, dabbed, or rolled, producing textures that range from delicate tonal transitions to bold, painterly strokes. The related oil print achieves a similar effect directly from gelatin hardened in exposure. These techniques appealed to early pictorialists for their ability to merge photographic precision with the emotional language of painting. Today they remain a niche practice, valued for their physical depth, unpredictability, and the sense that the artist’s hand has reentered the photograph.

Lith printing is an expressive variation of silver gelatin printing that replaces precision with controlled chaos. The paper is developed in a highly diluted lithographic solution, causing infectious development—a chemical reaction that makes shadows erupt suddenly while highlights stay soft and glowing. The result is a print with gritty shadows, warm or colored midtones, and luminous highlights that feel almost alive. Every print is unique, shaped by small differences in temperature, paper age, and timing. A few seconds too long in development can shift the entire balance of the print. Lith printing attracts artists who enjoy surrendering part of the process to chance; it turns chemistry into collaboration and transforms the photograph into something that looks less printed than time-worn, discovered, and deeply alive. This unpredictability is part of the appeal: each print feels discovered rather than produced.

III.In-Print Methods

In-print methods make the image on a physical matrix—plate, screen, or block—and then transfer it to paper with pressure. The legacy is tactility and edition discipline: plate impressions, ink relief, paper choice, and the printer’s touch all shape the result. There are dozens techniques in this category: woodcut, linocut, engraving, etching, aquatint, drypoint, mezzotint, photogravure, lithography, screen printing, monotype and offset - to name just a few.

We will only focus here on photogravure, screen printing, mono-printing and offset. These methods bridge photography and printmaking, opening the door to hybrid workflows and layered, crafted surfaces. Except for a mono-print, the defining principle here is the speed and repeatability of producing a series of identical artworks. Similar to the chemical reaction category, the art lies in setting up a process that produces identical prints despite the many variables involved - plate making, ink viscosity, pressure, humidity, plate inking, paper moisture, alignment, temperature, etc. A skilled printer can not only make one excellent print but repeat that quality across an edition. That reliability achieved through precision, control, and understanding of the process is what separates chance and beginners luck from a true craftsmanship.

Photopolymer (Solar Plate / Polymer Gravure)

Photogravure: The image on the left was produced by pressing the plate imprint (shown on the right) under tremendous pressure of an intaglio printing press; each new print requires the plate to be cleaned and re‑inked.

Photopolymer printing, often called solar plate or polymer gravure, bridges photography and printmaking. The process allows photographers and artists to make prints that feel handmade without abandoning the control of digital imaging. Unlike inkjet, which sprays ink onto paper, polymer gravure presses ink into it. The image sits within the fibers, leaving a subtle plate mark that gives the print weight and presence. It looks and feels like intaglio—rich blacks, continuous tone, and a surface you can run your fingers across. That physical impression immediately separates it from the smooth perfection of digital prints. The level of detail and tonal range is astonishing—a well-made print can easily be mistaken for a black-and-white photograph until you run your fingers along its edges and feel the plate impression. After all, this process descends from photogravure, the first technique developed in the 1880s that allowed photographs to be reproduced in ink and distributed as fine prints or in publications, a first Xerox machine, so to speak.

The process starts with a digital negative (inkjet print on a transparent film) and an aquatint screen, which together are exposed under UV light onto a photopolymer metal plate. After exposure, the plate is washed out, hardened, inked, and wiped by hand before being printed on dampened fine art paper with an intaglio press. The artist’s choice of paper and ink—carbon-heavy black, sepia, or warm pigments—sets the mood. Multi-plate color versions expand the process further, turning photographs into richly physical, tactile objects.

Compared to other image-making techniques, photopolymer printing requires specialized equipment that’s neither small nor easy to obtain. It needs a heavy intaglio press often weighing several tons, and large working space to handle plates, inks, and dampened papers. As a result, most artists who practice the process do so in shared print studios or collectives where they can access professional presses. This makes photopolymer printing relatively rare, even though the process itself isn’t especially difficult once the equipment is available. In terms of longevity, photopolymer prints are remarkably durable, made with oil-based inks on cotton papers that can last for hundreds of years.

Screen Printing (Silkscreen)

Screen printing, or silkscreen, is both a fine art technique and an industrial process—one of the oldest known forms of stencil printing. Its origins trace back to ancient China, around a thousand years ago, where stencils made from silk and human hair were used to apply decorative patterns to textiles and paper. The technique spread through Asia, evolving in Japan as katazome and reaching the West much later, where it was adapted for commercial printing in the early twentieth century.

In its modern form, a fine mesh screen is coated with a light-sensitive emulsion, exposed to ultraviolet light through a film positive, and washed to create a stencil. Ink is then pulled across the screen with a squeegee, passing only through the open areas. Each color is printed separately, layer by layer, until the image is complete. Every pass leaves a subtle relief—an accumulation of ink that gives screen prints their tactile surface and unmistakable physicality.

Artists and printers can adjust nearly every variable: mesh count for fine detail or thick texture, inks ranging from dense matte to metallic or fluorescent, and even “split-fountain” techniques that blend multiple colors in a single pull. The process invites experimentation but also demands discipline—each layer must align perfectly for the image to hold. The process is inexpensive—essentially just the cost of ink—and allows for precise and repeatable reproduction of images on paper, fabric, or any flat surface. Before digital printers existed, screen printing was the universal tool for visual communication. Schools and universities used it to make posters and announcements, governments used it for propaganda, and revolutionaries used it to spread dissent. Its simplicity, low cost, and immediacy made it the printing press of the streets.

Screen printing’s contemporary fame as an art process owes much to Andy Warhol, who embraced it in the 1960s precisely for its speed, reproducibility, and bold flatness. He chose screen printing because it represented industrial efficiency and the idea of identical mass production. It was fast, repeatable, and mechanical—everything traditional art was not suppose to be. It was the perfect medium for his view of modern life: art made in the image of mass culture. It allowed him to mass-produce his famous Marilyn Monroe portraits and other works on an industrial scale while still preserving the imperfections that made each print slightly different. That tension between mechanical repetition on industrial scale and human touch defines the medium even today. Screen printing remains a method where art and production, image and surface intersect.

Monoprint / Monotype

Monoprinting is the most direct and spontaneous of all printmaking methods. It’s essentially a drawing or painting made on one surface and transferred to another through pressure - an imprint in the most literal sense. The process merges the immediacy of painting with the tactile depth of printmaking. Each print is unique, one of one, with textures and tonal shifts that can never be exactly repeated.

At its core, monoprinting offers freedom. Unlike most printmaking, which depends on reproducibility, monoprinting celebrates the opposite—the unrepeatable mark, hence the name “mono”. It’s ideal for artists who want to explore gesture, texture, and improvisation without being bound to precise editions. The medium invites accidents and rewards intuition. Artists work additively or subtractively, building up or wiping away ink, sometimes pulling a second, fainter impression known as a ghost print. Techniques like collage, viscosity inking, or chine-collé can add further layers of texture and depth. Related relief and planographic methods—woodcut, linocut, or lithography—extend this vocabulary from bold carved lines to soft, drawn tones. In every case, a monoprint records more than an image; it preserves the gestures and decisions that brought it into being, holding the moment of touch between artist, ink, and paper.

Monoprinting also allows mix-media approch in photography - an ink, paint, or texture can be added, smeared, or lifted to alter the photograph itself - effects that feel alive in a way no digital tool can imitate. Every mark, pressure, and imperfection remains visible and felt. That immediacy connects the artist directly to the work, making each print a small event rather than a product.

Offset printing

Offset printing is a mechanical, lithographic, mass‑production process in which ink is transferred to paper via a system of cylinders. It remains the dominant method for commercial printing used for books, magazines, posters, and packaging because it delivers clean, sharp images at very high speed and low cost when produced in large volumes. Offset presses can print thousands of sheets per hour, typically using the four‑color CMYK process to reproduce full color. Each job therefore requires four separate printing plates—one for cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—making the initial setup costly and practical only for high‑volume runs.

The process relies on the principle that oil and water don’t mix. A flat metal plate (usually aluminum) is prepared so that image areas attract oily ink while non‑image areas attract water. The inked image is first transferred, or “offset,” from the plate to a rubber blanket cylinder, and then from the blanket onto the paper. This indirect transfer gives the process its name.

In the art world, offset printing has long been used for posters and photobooks. Although it cannot match the tonal depth and surface quality of fine inkjet or dark‑room prints, it excels at producing consistent, high‑quality reproductions at scale, though it is typically limited to paper types that do not rival the quality and variations used in fine‑art printing. It isn’t generally considered an art process but rather a tool for marketing and experimentation. It’s used to produce large numbers of copies that can be distributed cheaply or serve as a base for further artistic work using other techniques - screen printing on top, painting, spraying.

Conclusion.

This article introduced two key ideas that are essential for understanding and learning to appreciate art. The first is that, categorically speaking, there are only three ways to make a print: direct application, chemical reaction, and imprint or transfer. Within each category, countless branches and variations exist. Yet, these three fundamental methods give you a mental map of how any image comes into being. They help you see past technical terminology and focus on what’s physically happening between material and surface. Once you understand the process, you begin to understand what an artist is actually doing, what choices they’re making, and where skill and creativity intersect.

The second idea is that technique is not simply a set of tools but a system of thought that reflects the artist’s relationship to material, time, and idea. This idea adds depth to the map. Every medium demands a different balance between time, control, and chance. And tools and methods chosen by an artist are never neutral or random - they reflect the artist’s values and way of thinking through material and surface. Seeing technique this way connects the physical act of making to the artist’s philosophy and intent.

Together, these two concepts shift how we understand art - from something purely aesthetic to something grounded in logic, material, and intention, where matter, time, and thought come together to create meaning. As you master these two ideas, you’ll start to see more depth and purpose in art, and your expectations for each technique will grow with every new encounter. That play between expectation and reality becomes the basis for genuine appreciation of art - or perhaps the start of a beautiful affair with it.

Understanding Value Creation in Printmaking

It used to be that all photographs were prints. Today, however, most photographers no longer print their work, and printing is too often dismissed as unworthy of a ‘serious’ artist. Yet understanding the full chain of value creation in printing could change how prints are seen and valued—by collectors and photographers alike.

Sometimes talking about printing with other people reveals how little most people understand about the process of making a good print. Somewhere along the line, photography and print became blurred into a single idea. It used to be that all photographs were prints—there was no other way, and the words photography and print were interchangeable. Photography meant print. Period. Today billions of digital images are created each day, yet only a tiny fraction ever make it as prints, and those few that do, often end up as prints stuck to a fridge.

And this attitude isn’t limited to casual viewers—many photographers themselves no longer print their work or even see the point in trying. Too often, printing is dismissed as trivial, unworthy of a “serious” artist. Part of the blame lies with printer manufacturers and their decades-long marketing campaigns. We’ve been led to believe that printers are smart, almost magical machines: buy one, press a button, and a flawless print appears. Yet, anyone who has actually used a printer knows it’s nothing like that. You might get is a print, but it will not be what you’ve expected to see at all.

The truth is that a print is never simply ‘pressed out’ of a printer. A printer is a dumb machine: it knows nothing about the image it is producing, the paper it is using, the conditions in which it will be viewed, or whether the artist wants it more vivid, softer, or higher in contrast. It has no understanding of whether it is printing a volcanic landscape in Iceland or a cat. All of this must be decided and set by the printmaker. That’s why the same printer can produce a brilliant print in one person’s hands and a muddy, lifeless one in another’s. The artistry lies not in the machine but in the judgment and knowledge of the person guiding it.

The other reason for lack of understanding is the rise of fulfillment services with their enticing promise: “Just send us your file and we’ll ship the print to anyone, anywhere.” It’s a good pitch that many photographers fall for, but the product often falls short. The artist has no control, no visibility over what the customer receives, and the customer - believing the print came directly from Photographer X - rarely questions the quality. And without strict quality control - a print is no better than a poster. It is treated as a commodity and inevitably becomes one.

Printing is part of a larger act of translation. It starts from reality translated to a two-dimensional digital image, and back again into a physical object on paper as a print. Every stage of that translation requires both technical skill and artistic judgment. Every print carries the hand of the maker in every decision, and there is real art in that. And of course, none of it would matter without a strong image to begin with.

And here lies the paradox: the better the image and the better the print, the less visible the expertise behind it becomes. Canon and Epson understand this well, which is why they employ armies of brand ambassadors—photographers with strong source material whose work can be translated seamlessly into brilliant prints. That invisibility of labor and effortless success is one reason why prints are so often undervalued compared to drawings or paintings. People know far more about painters, paints, and their struggles than they do about photographers and printing challenges.

Yet understanding the full process might change how prints are seen. If more people grasped what goes into each print, more would value them, recognize them as art, and perhaps even fall in love with them. It is for this reason that I’ve written this guide. What follows is not a universal formula but a map—a sequence of five stages that begins with importing files from a shoot and ends with the framed artwork. Not every photographer follows all of them. Some stop at step1 or 3, others outsource certain steps in between. What matters is that each stage involves conscious choices, and those choices shape both the final result and the value of their art.

A high-level overview of the complete printing process.

Step 1: Selection

The first step is about narrowing down the images into a strong set of candidates for print. Most photographers are used to culling—sorting through and selecting their best shots—but evaluating with print in mind adds another layer. It’s no longer just about asking which images look great on a screen, but which ones will hold their strength on paper. Which images will look good on a wall? Which will stand the test of time?

This is also the stage where the selected files are batch-processed and given a first round of editing in software such as Lightroom: correcting white balance, adjusting the histogram, straightening, cropping, and removing obvious distractions. More detailed local edits, like skin retouching, are usually left for later steps.

To make this more concrete, let me give you an example. After a day of shooting I might come back with 2,000–3,000 images. Through several rounds of sorting, I cut about 90%, which leaves me with roughly 200 images. I process these in Lightroom, export them, and refine the selection again, this time with print in mind. At that stage, I might select only 30–50% as candidates for printing. Before moving on, I also try to form an idea of what kind of print each image might become - whether it’s something small, large, or better suited for an alternative process.

Step 2: Printing

Once images have been selected for printing, the next decision concerns how to produce them. This stage is often what people imagine when they think of “printing”: choosing the paper, the size, printer settings, and managing color. Most literature and workshops focus almost entirely on this step. Yet inkjet printing at home is not the only option. Options range from printing at home, sending files to a professional lab, or preparing digital negatives for alternative processes. Professional labs typically offer a far wider range of materials and the ability to produce larger sizes. They are also specialists in their offerings—papers, aluminum plates, acrylic glass, wood, canvas.

Paper choice introduces another layer of complexity to navigate. In an ideal world, one might print each image on every type of paper and at multiple sizes, then evaluate which combination works best. Reality, however, makes that impossible. Few can afford to test every option, which is why experience and competence are essential: they save both money and time while selecting the best medium for each image.

Knowing the intended use of the print—personal display, a gift, an exhibition piece, or a print for sale - influences which paper is most appropriate. Each scenario has different requirements and expectations. Conservation aspect is critical for prints intended for sale. Cotton-based papers are archival and long-lasting, but more expensive; wood-pulp papers are cheaper but less durable, yet perfectly fine for home prints where cotton based papers will be on overkill.

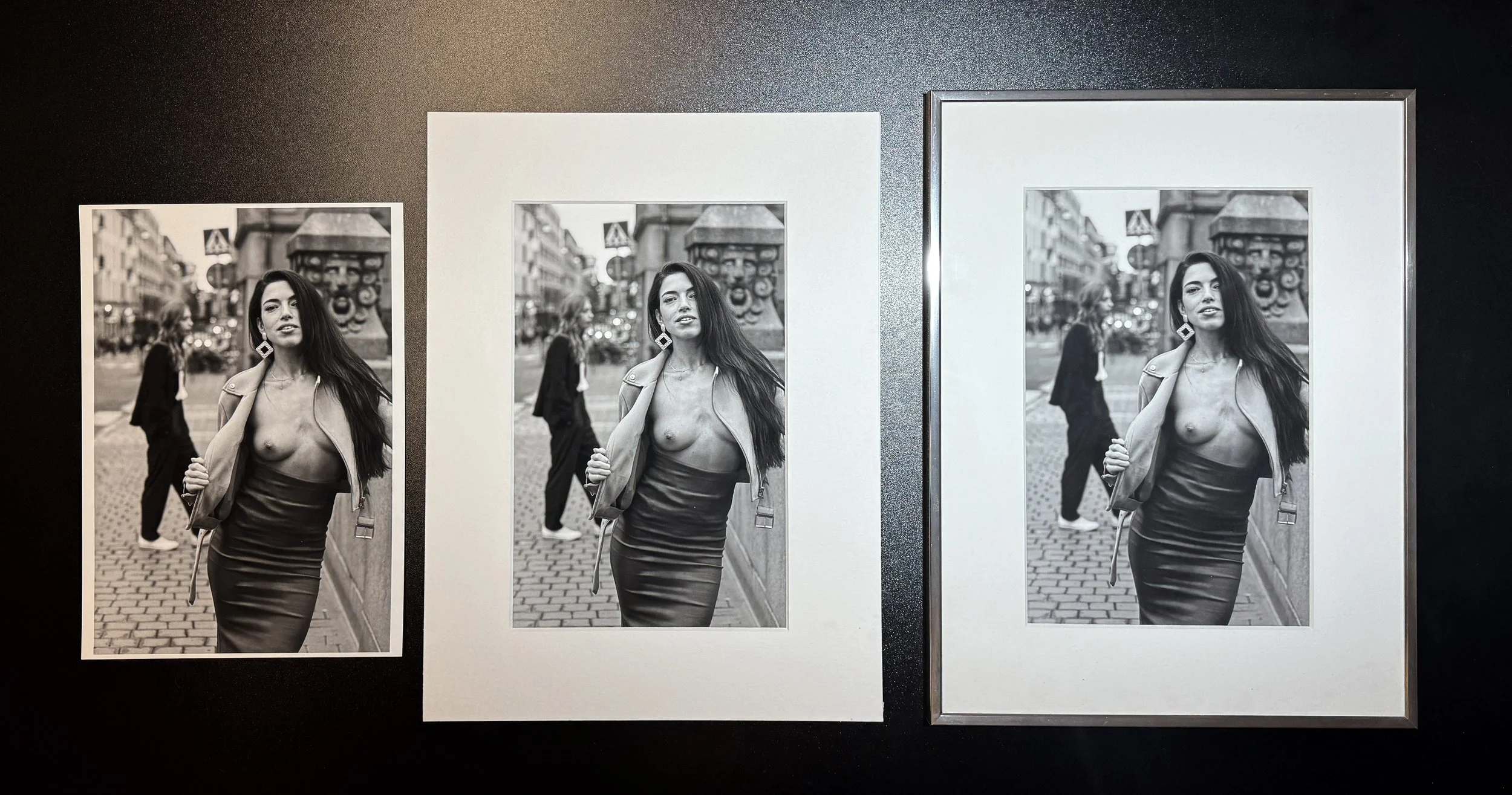

Example: From 100 candidates selected in the previous step, I will print 15–20 small 10×15 prints on different paper types. This first round eliminates weaker images and highlights the most suitable papers. The strongest 50 might then be printed at 10×15, from which around half are chosen to test at A4. At this size, flaws become more visible: focus issues, subtle distractions, or tonal imbalances that were not obvious at smaller scales. Some images return to Photoshop for correction and local edits before being reprinted. From the A4 prints, perhaps half progress to A3 prints. By the time printing reaches A2, only a handful images will remain. Many images have natural size limits: they work at 10×15, remain strong at A4, but begin to collapse at A3 or beyond. For an artist, it’s essential to know the point at which an image starts to degrade—and never offer prints beyond that threshold. Today’s AI upscaling tools can extend resolution, but resolution is not the real issue. What matters is how busy, engaging, and interesting the image remains at scale. The human eye adapts quickly: what looked striking when first seen at scale can become visually monotonous once the initial “wow” factor fades. That’s why painters and printmakers have long thought about “viewing distance” and “scale integrity”—the ability of a work to keep rewarding attention at different distances and over time.

In this workflow, my home printer capable of A2 is sufficient for most prints. Anything larger is sent to a professional lab. I have already printed an image in A3/A2 size and know that the image can hold its strength at larger size. Without this initial testing, ordering directly from a lab can feel like a gamble - you can never know what you’ll get back.

Step 3: Post-Print Modification

This stage is often overlooked, yet it opens an entire world of possibilities. A print doesn’t have to be “finished” once it leaves the printer. It can be toned, hand colored, overprinted, aged, or cropped. Gloss layer can be added to matte prints, or matte applied to glossy. Creativity is the only limit here. Post-print interventions have a long tradition in art photography and printmaking. Photographers and printmakers have often modified their work after printing to add uniqueness or character.

The reason many photographers skip this step today is simple: post-print processing is not part of the traditional photographic workflow or education. To do it well requires multidisciplinary knowledge, something few photographers possess. Broadly, these interventions fall into two categories: freehand modification and full-image manipulation.

Freehand modification includes drawing or painting directly onto the print. This demands a clear understanding of how different media interact with paper and ink: acrylic, oil, watercolor, inks, as well as the tools—brushes, markers, cotton swabs. It requires knowledge of color theory, blending, and application. Full-image manipulations, by contrast, are less demanding of artistic draftsmanship. Techniques like toning or second exposures rely more on chemistry and process than on hand and brushwork.

With post processing 10 identical inkjet prints can become 10 very different art objects. That’s what gives this step its creative potential: it breaks the idea of the print as a fixed, endlessly repeatable object. If two photographers print the same file, they will produce nearly identical images. But once post-print processing enters the equation, those same prints may diverge completely—each bearing the unique mark of its maker.

Example: I have toned prints in coffee, hand-colored with acrylics, watercolors, and inks, aged with heat or water. Of course, digital tools can replicate some of these effects, but the point here is not consistency—it is uniqueness. Each intervention adds individuality. It isn’t scalable, and from a business perspective it may not be efficient, but as a creative step it transforms a print into something truly unique.

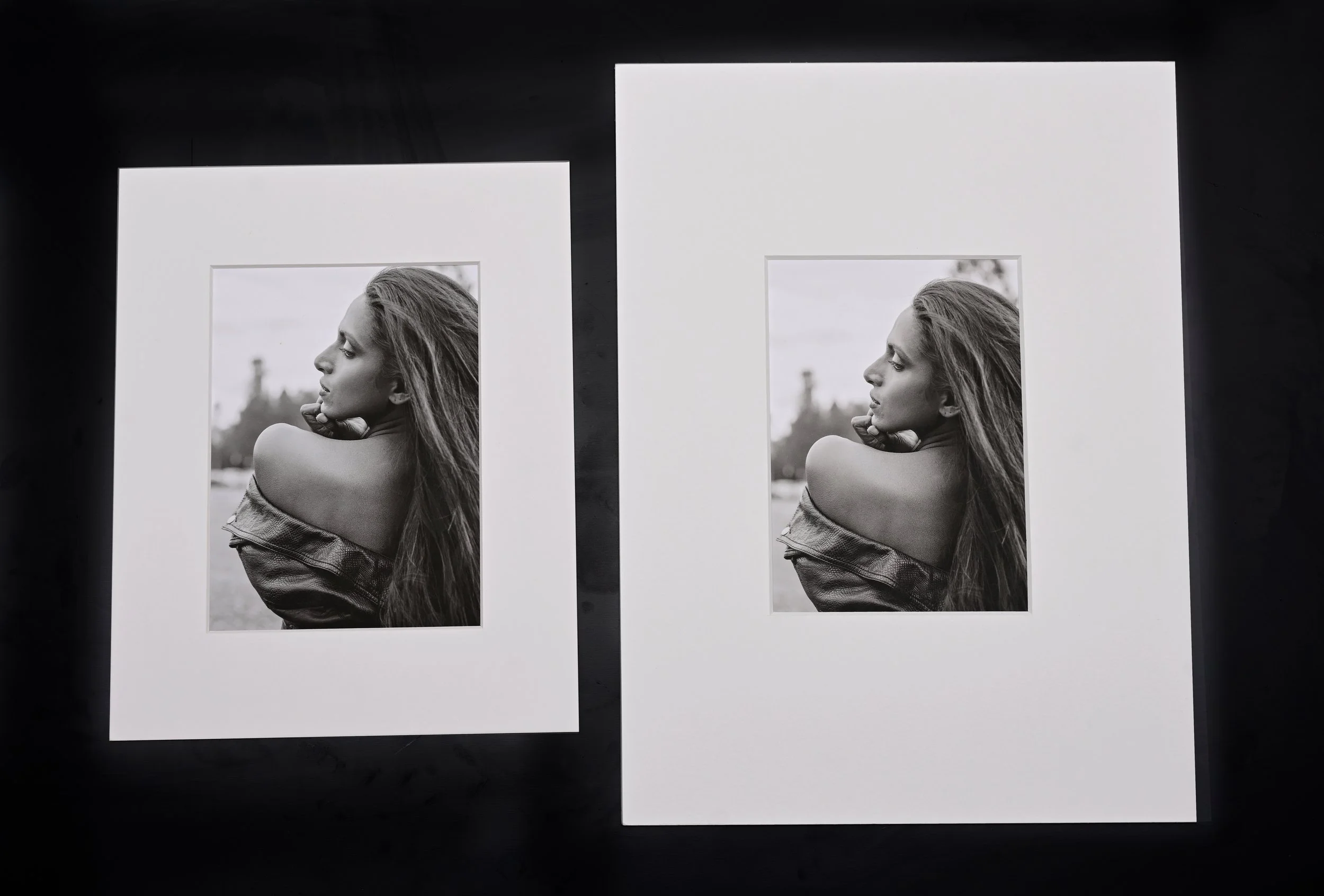

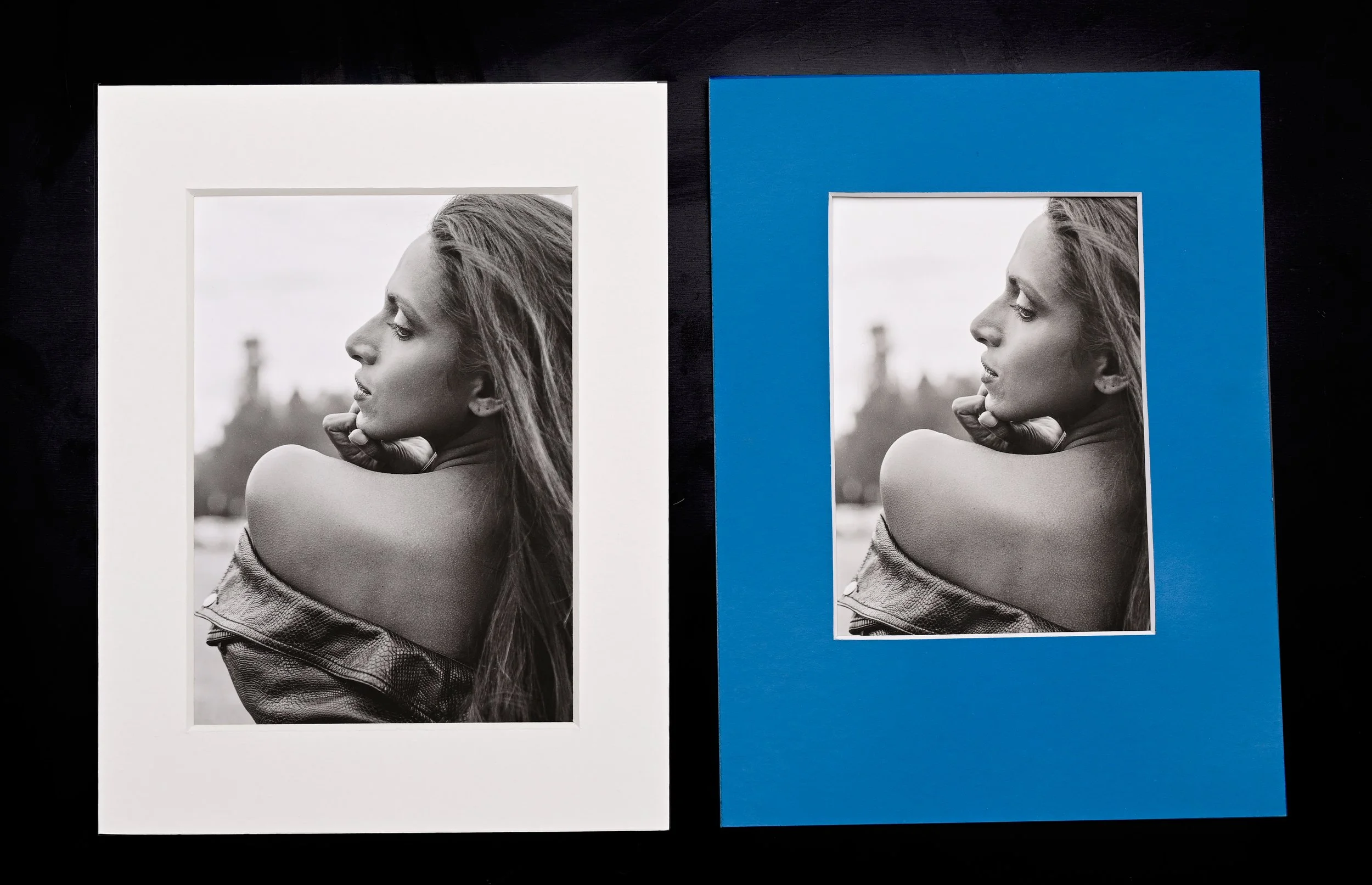

Step 4: Matting

Matting is often dismissed as something outside the printing process. It is seen as uncreative, something to skip entirely or outsource to a framer. But this could not be further from the truth—matting is the step that transforms a sheet of paper into a work of art. Done well, matting elevates a print from paper into something special. It becomes a permanent part of the artwork, not just a decorative border.

Matting is both perception and preservation. Think of packaging: the way a product is wrapped and presented shapes how we value it. Matting functions the same way for a print—it frames the image, sets the stage, and creates the context in which it will be seen. At the same time, mats create a physical barrier, protecting prints from touching the glass, from fingerprints, and from environmental wear.

The obvious question is then - if standard mats are available everywhere, why bother making your own? The answer is that doing it yourself teaches you about your images. Cutting and fitting mats builds an eye for proportion, balance, and how presentation changes meaning. Custom mats give you full control over framing, and the difference is immediately visible. This knowledge also makes you a better judge when you order matt services form someone else. With large editions, economies of scale inevitably demand outsourcing and uniformity, which dilutes the sense of uniqueness collectors value. Historically, this is exactly why smaller editions with visible signs of craft command higher prices.

Example: For me, matting is the ultimate commitment to the print: dressing it to impress, making it truly unique. I often cut and paint my own mats, experimenting with non-standard window ratios. This gives me complete control over how the print is presented.

Of course, practicality has limits. If I had to produce 50 or 100 identical mats, I would outsource them to a framer with cutting machines—after first designing the mat myself. There is no need to manually create 50 identical mats, but designing the first one by hand is invaluable process. Outsourcing only makes sense once I already know what I want. It is like a designer who spends months creating a chair or a dress but once the winning design is found, it can be reproduced in a factory on a mass scale and at a fraction of a cost.

This is also why I resist producing large editions in principle. With 10–15 prints, every copy can be made by hand. With 50 or 100, the pressure to automate and outsource grows, and the collector ends up with something less personal. A small edition means I spend far more time on each print than someone who is using a print fulfilling service. That additional time is my investment in the “best print” for the most demanding collector and it is why my prints are priced higher.

Step 5: Framing

Up to this stage the process has taken a digital file and turned it into a physical print on paper. Mixed artistic skills may then be applied to modify the print, and matting gives it both presentation and protection. Framing is the final step in this interdisciplinary process.Framing determines how an artwork will live in the world. It is what separates a poster from art. The same image, unframed, can feel casual or temporary; once framed, it gains weight, permanence, and status. That’s why even inexpensive prints or posters look “upgraded” when placed behind glass in a proper frame.

Framing is both protection—against dust, moisture, pollutants, and UV light—and the permanent home for a print. Creatively, it is also one of the most open-ended steps, capable of either elevating or undermining a piece. As the saying goes, bad framing kills great art. The framing options are nearly endless: materials, colors, sizes, depths, glazing.

The choice of frame depends on the type of print and where it will hang. Where will it be displayed? What color are the walls? What else will share the space? What kind of glass does it need—or should there be no glass at all? An artwork never lives in isolation; it is in constant dialogue with its surroundings, and the frame is what facilitates that dialogue. Museums and collectors invest in framing not only for its appearance but also to safeguard a work’s lifespan. For rare or valuable pieces, conservation framing is worth the investment, with museum-grade materials that protect a print for generations.

Today most people settle for thin, industrial metal frames. They are stylish, functional, and draw little attention to themselves. But historically, frames were treated as an art form in their own right—often inseparable from the artwork. That doesn’t mean a print today needs an ornate Rococo frame, but it does mean there is creative potential here. With modern 3D printing, and with skill in wood or metal work, highly sophisticated frames can be made today.

Ready-made frames are often sufficient, but custom framing is a completely different undertaking. A skilled framer blends craftsmanship with design and conservation knowledge, often advising on interior presentation as well as technical protection. Even a quick visit to a local frame shop reveals hundreds of possible custom frames—an easy way to see how different choices might reshape the way a print is perceived.

Example: I rarely ship framed prints. Framing is highly personal and best left to the collector’s own preferences. For personal prints that I hang at home, I often use Nielsen or Halbe premium frames. They are high quality and allow for easy image swapping. The original glass can be replaced with UV-protective acrylic, which also makes the frame lighter. Sometimes I omit glass altogether, letting the print be touched and experienced directly. I’ve also experimented with painting white frames in other colors, using both sprays and markers.

Conclusion

The point of this guide and overview is to give a bit more understanding of the steps involved in printmaking, but also to highlight the difference between photographers who handle every stage themselves and those who do only a few and outsource the rest. In art, the story behind the work is often as important, and sometimes more important than the object itself. If the image alone were what mattered, high-quality reproductions would sell for far more than they do. What we truly value is the connection to the artist. That’s why signed prints, hand-modified works, or editions with COAs (Certificates of Authenticity) command higher value.

There is a big difference between buying a print that has been made and sent by the artist and buying one shipped directly from a fulfilment lab. Knowing that an artist has mastered matting or post-print modification techniques helps explain why such prints cost more than something fresh from the printer. Skills like matting, alternative printing, or hand-finishing require practice, which costs time and money. Each adds an extra layer of uniqueness to a print. But if the market only rewards cheap standard output, there’s little incentive for artists to develop or maintain these skills. The result is a race to the bottom, where the cheapest print wins. This is a real dynamic - the abundance of cheap prints and automated fulfillment has pushed down prices, making it harder for handcrafted or deeply considered prints and artists to compete. This trend helps no one: photographers cannot sustain themselves or refine their skills, and collectors end up with mediocre prints that carry little artistic weight. In such a scenario, the art print competes with a poster as disposable home décor.

This framework can also be applied to other roles to understand value-creating activities in the production chain. A lab, for instance, doesn’t need to engage in image selection—their expertise lies in how best to print what is sent to them. A framer doesn’t need to know the printing process, as their specialization is in matting, framing, and glazing. Each stage has its own craft, and recognizing this helps reveal the full value chain.

An example of a photographer whose engagement with an image ends after the printing stage, outsourcing the rest.

An example of a lab’s full-service offering - only what to print is selected by a customer.

An example of a framing store offering.

What is a good print?

This guide is here to help you uncover what truly goes into creating an art print, how to choose the perfect piece for your space, and what makes a print worth your investment. By the end, you’ll…

This guide takes you through what goes into creating an art print, how to choose one that fits your space and taste, and what is really worth paying for. When you’re done reading, you’ll have the confidence and know-how to start your own print collection.

Buying an art print should be a simple and enjoyable experience, something you look forward to with excitement and anticipation. After all, art is about emotions and conceptual ideas that resonate with you. What makes owning art so appealing is its power to alter our mental states.

Yet, too often, buying art ends up being confusing or intimidating experience, especially if it’s your first print. People often see buying art as a gamble, where the only way to avoid losing is not to play at all. So, they steer clear of purchasing art altogether, fearing they’ll be taken advantage of or end up feeling duped. That is just sad, but it’s understandable given the nature of the art market.

Buying prints is really not hard. Find an image you love, pick the right size to fit your space, ensure it’s printed on quality materials, frame it, and you’re all set. That is all there is to buying a print. Unless of course you wonder if the price you’ve paid for it was fair. And it is a valid question. How can you tell if you’re getting a premium print at a fair price or an overpriced, low-quality one? How do you figure out what’s truly worth it? The truth is, you probably don’t, at least not when you’re just starting out. But that’s where this guide steps in, here to help you get up to speed quickly.

Remember, the goal of any purchase is to get the right thing at the right price. In the world of art, that means understanding the printing process and how value is created along the way. Once you learn what makes a print good, bad, or truly exceptional, you’ll never unlearn it—and you’ll be able to recognize exactly what’s worth paying for. Let’s get started!

WHY BUY PRINTS?

Size doesn’t matter. At least not for prints. Actually, scratch that. The bigger, the better… if bigger is better. What? You see, not every image is meant to be printed large. Some are designed to be small, intimate, and personal. Others demand to be showcased in grand sizes and lose their appeal when scaled down. And then there are those that work beautifully in any size. Welcome to the art of choosing the perfect print, and yes, the perfect size too.

Welcome, and let’s address the big question: why buy prints at all? Why do some people choose to spend money on prints when they could use it to buy other things or experiences? Are they wealthy? Art scholars? Social media influencers? What makes them see value where others don’t? These are excellent questions to kick off this conversation.

If we exclude art posters, nearly 99% of people have never bought a print in their entire lives—in fact, not just prints, but no art at all. Ever. This makes print collectors a truly rare breed. But luckily, we have some data to help us understand them better. According to Art Basel’s 2018 Report (which focuses mainly on paintings, not prints), the top five reasons people buy art are aesthetics, passion, supporting an artist, expected return on investment, and portfolio diversification. When it comes to prints, financial motivations can almost entirely be ruled out—very few prints will ever appreciate enough in value to be considered a true investment asset. That leaves aesthetics, passion, supporting an artist, and social reasons. Let’s look at them closely.

Aesthetics often come down to a simple desire: filling a space with art. This might mean choosing a black-and-white print, a bold red or blue piece to match an interior, or even opting for an image of a female figure that complements the room’s vibe. In these cases, the art buyer is rarely an expert in what they’re acquiring, the goal is on filling a spot on the wall rather than acquiring any particular art itself. For instance, a home decorator might recommend or purchase art for a client to create a specific mood or atmosphere within their home. You might be surprised by how often art is purchased simply based on a specific color or combination of colors.

Passion, on the other hand, is purpose-driven and fueled by curiosity. It might arise from a fascination with a certain topic or place, specific print techniques, unique materials, particular models, or the work of a favorite photographer. This type of purchase is often calculated based on the personal joy or meaning the piece will bring over a lifetime. A print can become a powerful reminder of something significant, transport the collector to a particular time or place, or serve as a gateway to something greater—an exploration of craft, art, creativity, the human drive for expression, self-discovery, and authenticity.

For these collectors, a print becomes more than just an object; it’s a story, a piece of their life, and a reflection of their values. They can spend hours talking about their favorite prints, passionately recounting the emotions and connections tied to each piece. These individuals draw energy from art—it’s their escape, their solace, and their way of coping with the ordinary grind of life. For them, art is not just decoration; it’s a bridge to something bigger than the everyday. Many collectors who buy landscape art prints often have a personal connection to the place depicted, which inspires them to have it framed and displayed in their home. Fans of nude models do the same—each new purchase becomes part of their collection, deepening their unique story and personal connection to the place or person captured in the art.

Supporting an artist is a straightforward motivation. This happens when a purchase is made not for the print’s aesthetic appeal or a personal passion, but out of a belief in the artist and their work. It’s a value-driven decision, rooted in thoughts like, “I’m not a fan of their style, but I believe in their vision and want them to continue.” In such cases, buyers may not fully understand the artistic or monetary value of what they’ve purchased. Instead, the act is one of patronage, sometimes resembling charity, driven by a desire to support creativity. Many friends and relatives of artists fall into this category—they buy art, but rarely grasp what it is they’ve acquired and what to do with it.

Finally, there’s the social aspect, where people buy art because they feel it’s expected of them. Whether it’s a status symbol or a situational decision, social motivations are often influenced by external pressures or trends. For instance, certain institutions or families might purchase prints on a trendy topic, not because the art brings them joy, but because they don’t want to appear out of touch or be left behind.

Clearly, out of the 4 main reasons to buy art, it’s the passionate collector who experiences the most joy from purchasing, owning, and curating a collection. This is someone who consciously chooses to spend money on specific pieces, guided by their own criteria and personal satisfaction. Which brings us to the next big topic - money.

There’s a common misconception that collecting art has to be an expensive hobby. Or that is some upper class, bohemian, or academic activity. It is not, and specially not art prints. By eliminating the idea of art as an investment, what’s left is art for pure pleasure. And most prints don’t have to break the bank to have an impact on you. While there are very expensive prints, like large-format prints on metal or premium plexiglass for $3,000 or more, most prints cost under $1,000, with the vast majority priced below $500. This isn’t an insignificant cost, but it’s attainable for many people with the right prioritization. What I mean is that it’s absolutely possible to acquire a very good print for $500, and in this article, I’ll show you exactly how to do it. Remember, the true value of a print isn’t just in its appearance or price—it’s in who you become by owning it. Few things can enrich your life in the same way art does.

Collecting art as an emotional journey

Ultimately, collecting art is not a destination but a journey. As we grow and evolve in our social, economic, and personal lives, so too do our motivations and needs for art. Art is more than something that simply hangs on a wall—it transforms the spaces we live in, provokes thoughts we might have been afraid to explore, and becomes an integral part of our existence. It speaks to who we are, challenges us, and dares us to dream. Collecting art is about moving forward, discovering, and becoming.

Collecting art is a dynamic and deeply personal process. It’s not just about accumulating pieces; it’s about allowing art to influence and enrich your life, while discovering what resonates with you in the moment. Some artworks enter our lives at just the right time, creating an immediate impact and adding meaning we didn’t know we needed. Others grow on us gradually, becoming more significant as time goes on.

Over time, some pieces may fulfill their purpose, paving the way for something new. This evolving relationship with art requires an openness to new experiences, perspectives, and potential acquisitions. Collecting art means planning to expose yourself to new works, exploring possibilities, and remaining open to the unexpected power art can have on your life.

The 4 elements of a good art print

Now, let’s talk about the four key elements that define a professional art print. If any of these components are poorly executed or missing, the value of the print is significantly diminished. Understanding these elements will give you a clearer picture of what makes an art print distinct from an IKEA poster and help you know what to look for when selecting one. These four elements are: the image (or negative), the printer, the paper (or medium) used for printing, and the presentation (including matting, framing, and glass). Before we go any deeper into each of these elements, let me introduce you to a few concepts that will guide us along the way.

Print as a product

At its core, an art print is a product. And like any product, it involves three key components: an idea, execution, and presentation. A shot was taken, the print was created, and it was framed with a specific goal in mind: to become something desirable and meaningful. Ultimately, each print has, or at least should have a purpose to exists. It might aim to decorate, inspire, delight, or provoke deeper emotions. It has to do something, otherwise it is useless as a product.

Think about it: why does an IKEA poster cost a fraction of a professional print? After all, it might even be the same image. The difference lies in the job it’s meant to do and the care that goes into its creation. A print sold at IKEA is "hired" to do a very different job than a professional photographer’s print. These cater to distinct demographics with entirely different motivations. IKEA knows this, and so does the photographer.

The concept of "hiring to do a job" is a marketing idea that emphasizes how customers don't just buy products or services; they "hire" them to fulfill a specific need or solve a problem. For example, when someone buys a drill, they’re not interested in the drill itself but in creating a hole in the wall—a means to a deeper purpose, like making their space feel cozier or more organized. This concept underscores that every purchase satisfies not only functional needs but also emotional and social ones, such as projecting a certain image, fostering comfort, or achieving personal satisfaction.

At IKEA, customers buy prints as convenient, affordable wall decorations. A professional print, however, is an entirely different product. It delivers the full experience—the craftsmanship, the quality, the story behind its creation, and the emotions it evokes when displayed. It is not a casual purchase to fill a kitchen wall. A professional print embodies the skill of the photographer and printer, the meticulous selection of materials, the precision in its presentation, and the authenticity in every detail. It is designed to communicate emotion, with no compromises made to achieve this. What you pay for is purity—comparable to lossless audio or 4K video. A professional art print exists in its purest form, delivering unmatched quality and detail.

By contrast, an IKEA print is "optimized" to be affordable and widely appealing. Its image, size, and colors are "compressed" to meet mass production criteria, ensuring it fits into any setting without challenging its buyers. This approach makes it accessible but strips away the individuality, craftsmanship, and depth that define a true art print. Despite originating from the same source material, these are two entirely different products. They might appear similar at a glance, but they couldn’t be further apart—differing vastly in price, quality, and the emotions they evoke. One is a disposable decorative item, the other is a carefully crafted piece of art.

1.NEGATIVE - THE ORIGINAL SOURCE

The main reason anyone falls in love with a print and wants to own it is, of course, the image itself—the negative. If the original image isn’t strong, no amount of technical perfection in the printing process can save it. By “high quality,” I don’t necessarily mean technical flawlessness. It’s about the energy, vision, and connection the image conveys—something that resonates, inspires, or moves you. A great image retains its power, whether it’s printed on cheap poster paper or as a small 10x15cm print. This is the same principle behind many successful ads and branding campaigns: hire the best photographer you can afford, and everything else falls into place. A great shot can communicate an entire story or emotion, whether it’s featured as a page in a magazine or displayed as a billboard the size of a building. Ultimately, it’s the image and what it represents that draws people in, far more than the print itself.

So, the first step in collecting print art is finding an image that truly speaks to you. It should evoke positive emotions, connect with your memories, or reflect something deeply personal. With nudes, for example, the image might remind you of someone you know, stir memories of youth, or evoke admiration for the human form. Art can also shift your perspective, awaken dormant dreams, or draw you into the artist’s raw intent and emotions, making you a part of their vision. When the energy of an image aligns with you as a viewer, that’s when art becomes powerful and personal.

Consider this: compared to all other types of photography, nudes are an incredibly challenging area to master. There are no YouTube channels dedicated to discussing what makes a good nude, and online courses are almost nonexistent. While there are excellent photo books on the subject, there’s a noticeable lack of theoretical texts and foundational principles, unlike other genres of photography. That said, there are a few insights that can be distilled into key principles.

Rule 1: most nudes that look appealing on a screen won’t translate into good prints. The power of a print lies in its ability to resonate with your shifting states of mind, day after day, as it hangs on your wall. In contrast, images on a screen are designed to be swiped past or viewed for just a few seconds. They tend to be simpler, more direct, and often more explicit. For example, an open-leg nude might grab your attention on a screen, but as a wall print, it will likely bore you within a week.

Rule 2: most images in photo books won’t make great wall prints either. Images in books are curated to follow a sequence and tell a story. Some might work as standalone prints, but many are included to provide context or support the narrative. You may love an image because of how it fits within the book’s flow, but take it out of that context, and it can fall flat, losing all its energy. Even in a highly curated photo book, where only the best images made the cut, perhaps one in ten—or even one in twenty—might have the strength to stand alone as a wall print. This highlights just how difficult it is to find a truly good print.

Rule 3: good nude print is almost always a black-and-white print. This isn’t due to some outdated notion of what qualifies as art or nostalgia for classic prints, or some other BS. It’s because bare skin inevitably triggers specific thoughts in our brains, and we want to steer clear of those predictable patterns. A great print should evoke something new each time you see it, not lead you back to the same thought day after day. Black and white strips away distractions, inviting a deeper, more layered engagement with the image. It makes the familiar less familiar and removes the visual hierarchy created by colors that we learned to respond to.

Rule 4: Not all black-and-white prints are art. Beware of pseudo-artists who rely on the black-and-white aesthetic to disguise mediocre work. Converting a bad image to black and white doesn’t magically transform it into art. The essence of a great photograph lies in its composition, lighting, the model’s expression, pose, and attitude—not in the presence or absence of color. Black and white can only enhance what’s already there; it cannot create substance where there is none.

Rule 5: Don’t mistake a model with great genetics for a great print. Many beginners fall into the trap of confusing an image of a genetically blessed model with a strong photography. But that’s not how it works. While exceptional genetics is a gift, hand a camera to 50 people, and you’ll end up with almost identical “great shots.” of that model. She will likely look good in all of them, but that doesn’t demonstrate skill—it merely showcases access. If the measure of a photographer’s talent is reduced to having access to the best models, it misses the true essence of the craft entirely.

The reality is quite the opposite: a great photographer doesn’t rely solely on exceptional genetics; they discover unique and unconventional ways to convey beauty and express their vision in any setting. The art often lies in the contrast between what’s expected and how it’s executed. Ask yourself: if a different model were in this shot, would it still be a strong photograph for you, or is it just the genetics that draws you in? And take it a step further: if it’s the genetics, could another photographer have captured this person’s beauty even better?Don’t reward mediocrity with your wallet. Pay for work that reflects real creativity, skill, and vision.

Take your time. Explore a variety of prints. Let yourself be drawn to something that stirs something deep within you—something you feel will enrich your life simply by being a part of it. That’s the true essence of art: not just decoration, but a portal to another world, a reflection of another self, offering a glimpse into something deeper and transformative. When you discover that image—one you can analyze, defend, and truly desire to own—it becomes personal. It becomes yours.

When you’ve chosen an image you love, the next step is to consider the aspect ratio—essentially, the image’s proportions—and the size of the print you want. These two factors work together to shape how the artwork will look and feel in your space, influencing both the composition of the image and its overall presence in the room.

Different croppings of the same image create slightly different stories. The traditional ratio on the right includes more ground and sky, but does this extra context add value, or can we do without it, as seen in the square crop on the left? Which one is more appealing to you? Why?

A camera’s original rectangular photo can be cropped into different ratios, each highlighting specific parts of the image and altering how you experience it. You see this all the time in fashion ads: the same photo might appear vertically in a magazine but horizontally on a billboard. This process, called cropping or trimming, can dramatically influence the focus and balance of an image.

For example, a square crop feels balanced and harmonious, drawing attention to the central elements, while a wide panoramic crop might isolate the subject from its surroundings, creating a sense of space and expansiveness. Cropping is all about controlling where the viewer’s attention goes and reshaping the story the image tells.

The original aspect ratio isn’t always the best choice. In some cases, thoughtful cropping can elevate an image’s impact by focusing attention or removing distractions. As discussed before, nudes that grab your attention on a screen might not translate well into prints for your space. Cropping can emphasize or downplay certain areas of an image, significantly influencing how it’s perceived.

As the medium shifts from screen to paper, aspect ratios often need to adapt. Exploring different variations of the same image can reveal the format that best aligns with your vision and suits the environment where it will be displayed. For instance, one room might call for a square format, while another could be better suited to a panoramic layout.